Researchers in Australia's University of Sydney have found a way to manipulate laser light at a fraction of the cost of current technology. The discovery could help drive down costs in industries as diverse as telecommunications, medical diagnostics and consumer optoelectronics.

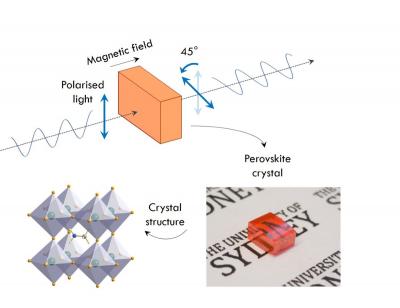

The polarization of transmitted light is rotated by a crystal immersed in a magnetic field (top). The perovskite crystal (bottom right) rotates light very effectively, due to the atomic configuration of its crystal structure (bottom left)

The polarization of transmitted light is rotated by a crystal immersed in a magnetic field (top). The perovskite crystal (bottom right) rotates light very effectively, due to the atomic configuration of its crystal structure (bottom left)

The research team, led by Dr Girish Lakhwani from the University of Sydney Nano Institute and School of Chemistry, has used inexpensive perovskite crystals to make Faraday rotators. These manipulate light in a range of devices across industry and science by altering a fundamental property of light ' its polarization. This gives scientists and engineers the ability to stabilize, block or steer light on demand.

Dr Lakhwani said: 'The global optical switches market alone is worth more than $4.5 billion USD and is growing. The major competitive advantage perovskites have over current Faraday isolators is the low cost of material and ease of processing that would allow for scalability.'

To date, the industry standard for Faraday rotators has been terbium-based garnets. Dr Lakhwani and colleagues at the Australian Research Centre of Excellence in Exciton Science have used lead-halide perovskites, which could prove a less expensive alternative.

'Interest in perovskites really started with solar cells,' said Dr Randy Sabatini, a postdoctoral researcher leading the project in the Lakhwani group.

'They are efficient and much less expensive than traditional silicon cells, which are made using a costly process known as the Czochralski or Cz method. Now, we're looking at another application, Faraday rotation, where the commercial standards are also made using the Cz method. Just like in solar cells, it seems like perovskites might be able to compete here as well.'

In their paper, the team shows that the performance of perovskites can rival that of commercial standards for certain colors within the visible spectrum.

'As part of the ARC Centre of Excellence in Exciton Science (ACEx), we benefited from the exchange of ideas through this high-caliber center,' Dr Lakhwani said. Collaborators included the ACEx groups of Professor Udo Bach at Monash University and Dr Asaph Widmer-Cooper at Sydney, as well as the Professor Anita Ho-Baillie group at UNSW. Professor Ho-Baillie has since joined the University of Sydney as the inaugural John Hooke Chair of Nanoscience.

'We've been looking into Faraday rotation for quite some time,' Dr Lakhwani said. 'It's very difficult to find solution-processed materials that rotate light polarization effectively. Based on their structure, we were hoping that perovskites would be good, but they really surpassed our expectations.'

Looking ahead, the search for other perovskite materials should be aided by modelling.

'For most materials, the classical theory used to predict Faraday rotation performs very poorly,' said Dr Stefano Bernardi, a postdoctoral researcher in the Widmer-Cooper group at the University of Sydney. 'However, for perovskites the agreement is surprisingly good, so we hope that this will allow us to create even better crystals.'

The team has also performed thermal simulations to understand how a real device would function. However, there is still work to be done to make commercial application a reality.

'We plan on continuing to improve the crystal transparency and growth reproducibility,' said Chwenhaw Liao, from UNSW. 'However, we're very happy with the initial progress and are optimistic for the future.'